The de Grainville manuscripts

It has been translated a number of times, sometimes partially, sometimes inaccurately; but never as completely as this. M. R. Osborne has already gained a reputation as a foremost exponent on the work of Pasqually, and his previous translations of seminal works associated with Pasqually’s Order have demonstrated both his depth of understanding and his ability to provide us with accurate English renderings of these important works.

The book is divided into two distinct sections. In the first, the Introduction, Osborne provides one of the clearest outlines of the Order of Elect Cohens I have ever seen. He gives us a background to the author and puts the manuscripts in context. While discussing the theological underpinning of the Order, he discusses La Chose, the mysterious power or being at the very heart of the work. In his discussion of the work of the Cohens, he takes care to stick to the facts and avoid both conjecture and a detailed explanation of the rites which in my opinion, is the right path to take, since delving too deeply into the minutiae of what were extraordinarily elaborate and detailed daily activities, would detract from the overall purpose of the Order. This is one instance where staying in the helicopter at thirty-thousand feet is a wise decision. This isn’t to say that Osborne doesn’t have strong opinions which he is only too happy to share!

However, the second part of the work, the translation itself, is free from conjecture, and demonstrates pure academic restraint, for which I am grateful. Determined to provide us with the most accurate possible version of the text, Osborne provides the original manuscript in the difficult handwriting of an eighteenth-century soldier on the one page, providing the translation on the other. This both allows us to marvel at the effort involved in transcribing, then translating this difficult work into modern and comprehensible English; and also affords us the opportunity to double check the translation if we wish. That openness is refreshing.

This is a book which the serious student can read from cover to cover, and also a reference book which the academic – or practitioner – can use to support questions or particular areas of interest. The work itself is provocative, and it is necessary to remember the times in which these Masons lived to truly appreciate the idea of burning dismembered animal heads in a room at home; or just how demeaning the ‘Outline of a woman’s reception’ was in the context of Pasqually’s worldview (but at least the Order did accept women…)! In another vein, de Grainville’s dissertation on music which begins the manuscript, and his later description of a singular dream provide insight into the author and his frame of mind. Of particular interest to the exegete will be unearthing the passages which Robert Ambelain clearly used when writing his famous reconstruction of the Cohen Rituals in the 1930s; and Robert Amadou included in his series Les Fonds Z.

All in all, this superb book will be many things to different people. It will speak equally to students of Masonic history, to practitioners of the neo-Cohen Orders in existence who wish to understand more about the origins of their Order, and to anyone keen to gain an insight into the thinking of a group of religious Masons at a time in history when both were exposed to ridicule by the vanguard of the Enlightenment.

Osborne has indeed done us all a great service.

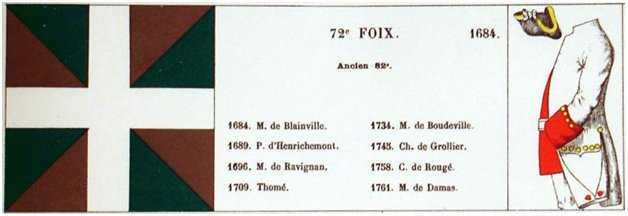

By the way, á propos of nothing, I notice a pair of brothers who might be part of the de Granville family! Guillaume-Balthasar Cousin de Granville (1745 – 1828), who went on to become Bishop of Cahors for many years; and Jean-Baptiste Cousin de Grainville (1746 – 1805), also ordained a priest and destined to follow his brother, but who lost his faith during the French Revolution and committed suicide in 1805. He was famous for writing the book Le Dernier Homme (The Last Man) published posthumously, which was the first modern novel to depict the end of the world. Notably, these two brothers were the sons of ‘an army staff officer’. Now, our de Grainville would have been barely 18 when the first son was born, but this is not that unusual in those times. While this may be a ‘hareng rouge’, the coincidence might warrant further research!

No Comments