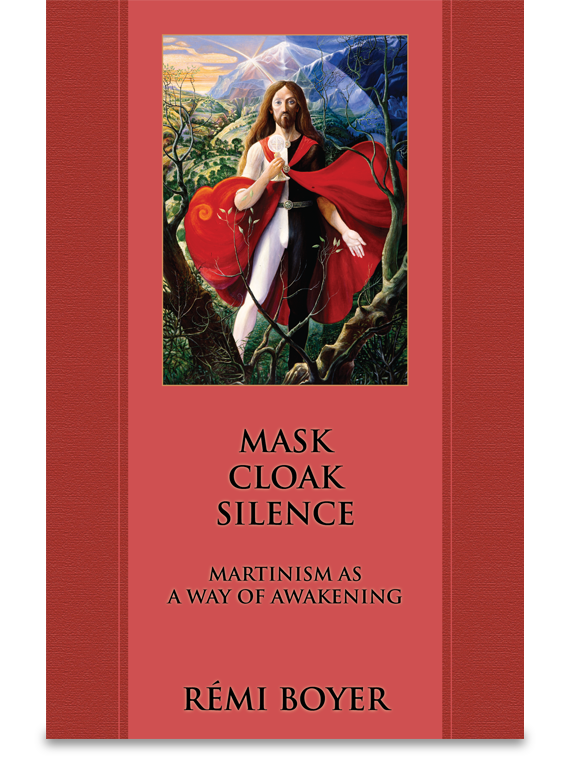

Mask Cloak Silence: Martinism as a Way of Awakening

I am delighted to announce to publication by Rose Circle Publications of the translation of a seminal French book by the renowned esoteric author and practitioner Rémi Boyer, expertly realized by Michael Sanborn, who previously brought us Boyer’s intriguing book about Freemasonry.

In 1863, Edward Burton Penny translated the correspondence which passed between the Unknown Philosopher, the nom-de-plume of Louis-Claude de Saint-Martin, and Kirchberger, Baron von Liebistorf, in his work ‘Theosophic Correspondence.’ This work has never been out of print. I can similarly hope that this profound work by Rémi Boyer will be read by students of Saint-Martin and Martinism in the coming centuries.

This series of books includes Freemasonry, Martinism and the Rosicrucians (or Rose-Croix). Last year saw the publication in English of Boyer’s book on Freemasonry; and this year we see his seminal work on Martinism.

Martinism began as a uniquely French phenomenon, born out of the mind of Saint-Martin, whom it is believed had a small number of like-minded friends, and who also practiced a form of initiation into his system just prior to and after the French Revolution. However, it wasn’t until Dr. Gérard Encausse – better known as Papus – in the latter part of the 19th century that the notion of Martinism both became codified into a quasi-Masonic Order, and started flourish both in France and abroad.

While the Order predominantly focused on esoteric theosophy and debate in France, its Anglo-Saxon cousin fared less well. Its first proponent in the United States, Eduard Blitz, wanted to transform it into a traditional Masonic Order with many different Grades. This didn’t sit well with Papus and his Supreme Council, whose experience of French Masonry was less than stellar. As a result, the mantle of leadership in the US was passed to Margaret B. Peeke, a populist esoteric writer, and which also made the overt point that, being led by a woman, the Order most certainly wasn’t Masonic. Like the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the choice of a woman to be a leader in the Order was ahead of its time.

However, the main thing the Order lacked was education, and apart from a series of short lectures on general esoteric knowledge, popularly known as ‘The Conventicles,’ little original Martinism education – other than the rituals themselves – ever made it across the ‘pond’.

Meanwhile, scholarship and original thought proceeded apace in France. Such luminaries as Paul Sédir, Dr. Marc Haven, René Guenon and many others, later replaced by Robert Ambelain and other luminaries, continued the tradition of writing about the philosophy of the Order; while the historic side was masterfully covered by René le Forestier, Alice Joly, Robert Amadou, and the chair of Esoteric Studies at the Sorbonne, Prof. Antoine Faivre. Now we have Rémi Boyer, Serge Caillet, Jean-Marc Vivenza and others who keep the flame alive and add to our understanding of this important Masonic, Rosicrucian, Theosophical and Esoteric tradition.

With such an embarrassment of riches on the French side, it is curious that the English-speaking world lags so far behind in this field of study. Yet we must remember that a society pervaded by philosophical though and esoteric nuance is not exactly an Anglo-Saxon trait, where books on ‘getting rich quick’ will always outsell books on critical thinking or self-actualization.

The body of the work itself will both inspire and give much food for thought. Providing extracts from the rituals and the commentaries upon the sources and the inspiration to which they give rise, the work is transcendental, as it is meant to be. It is a glorious synthesis of history, an explanation of the symbolism and a source of practical ideas which has hitherto been absent in the English-speaking world. Its side journey into Gnosticism and the resurgence of the Cathar Church is particularly informative.

However, it is the Appendices which truly move us from theory to practice, and the exercises they contain are to be commended. The book concludes with a Bibliography which, while mostly citing the many French works on the subjects, also references an increasing number of books becoming available in English. However, it must be said that most of the books listed are source materials. What we lack is the vast – and growing – library of books in French focused on the praxis of these techniques, and how Martinism is both relevant and critical to a world which seems to have lost its purpose and its place in the universe.

As an experiential book about Martinism and its practices, unique in the English-speaking world, I cannot recommend this book highly enough.

No Comments